Have you ever visited a place where each day brought tranquility and new wonders?

And let you feel the joy of just quietly being?

This past September (which seems like years ago now…), Scoutie and I went to Amherst Island and stayed in a unique cottage in the trees for a week.

Despite the chilly autumn nights, we were blessed with warmth and sun almost every day as well as deserted roads and beaches. Just the way we like it.

Amherst Island is located in Lake Ontario, just 10 kilometres west of Kingston, Ontario, and 3 kilometres offshore from the mainland. At 66 square kilometres in size, it is inhabited by just 450 residents, which magically doubles during the summer months with ‘fair-weather’ islanders.

You quickly notice that there is both history and modern life on this island as it is dotted with slick wind turbines and aged dry laid stone walls - one points to the future, the other to the past.

The island is buzzing. Opponents of the turbines say it’s the whirring that comes from the giant machines, but I couldn’t hear them. The buzzing I heard was the low hum of history, of lives lived, quiet modern-day islanders going about their business — sheep farming, harvesting hay, enjoying their retirements, delving into their own genealogies, volunteering at the local radio station, running the corner store or the summertime cafe.

In the earliest times, Amherst Island was known by local indigenous people as Ka8enesgo, translated as ‘big, long island’. But a quick search of the internetz gives us precious little else about its pre-European history.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, when the French were busy exploring (and claiming) the length and breadth of the eastern North American continent, this island was known as Isle Tonti, named after the Italian-born Henri de Tonti whose wealthy parents got involved in some political treachery and fled to France around 1650. De Tonti gained notoriety as the lieutenant and sidekick to the more well known French explorer and fur trader, Rene-Robert Calvelier, Sieur de La Salle. They were the first Europeans to navigate the upper Great Lakes, sailing south down the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, eventually claiming Arkansas and Lousiana in the late 17th century for Louis XIV, the King of France. Despite having lost a hand in a grenade explosion while fighting in Sicily during the Franco-Dutch War, taken prisoner for six months by the Spanish, being stabbed by the Iroquois while negotiating a peace treaty and being shipwrecked on the shores of Lake Michigan, he continued his career corralling enterprising fur traders, helping to build outposts and forts for the French, and basically either fighting or negotiating with the Iroquois. With a curved iron prosthesis for a hand, he was the original Captain Hook.

With the heightened fighting between the French and English along the St Lawrence, for access to each others trade routes, forts and outposts, it was inevitable that Isle Tonti be renamed in the late 18th century. Indeed, in 1792 the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, decreed that the largest islands that met the St Lawrence River in Lake Ontario be renamed after great British Generals of the Seven Years War: Wolfe, Amherst and Howe.

Jeffrey Amherst is now a contentious figure in Canadian history primarily because of his (likely not unique) view towards indigenous people. You can read about his illustrious career in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography here. He was a contemporary of General Wolfe, who is credited with defeating the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City, but it was Amherst who was victorious for the British in many other battles, most notably the fall of Louisbourg in Cape Breton. He spent only five years in North America (1758-1763), but not before he had written, thereby securing to Canada’s archival history, his thoughts towards indigenous peoples:

“Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them."

And then, to a British Colonel:

"You will do well to try to inoculate [sic] the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.”

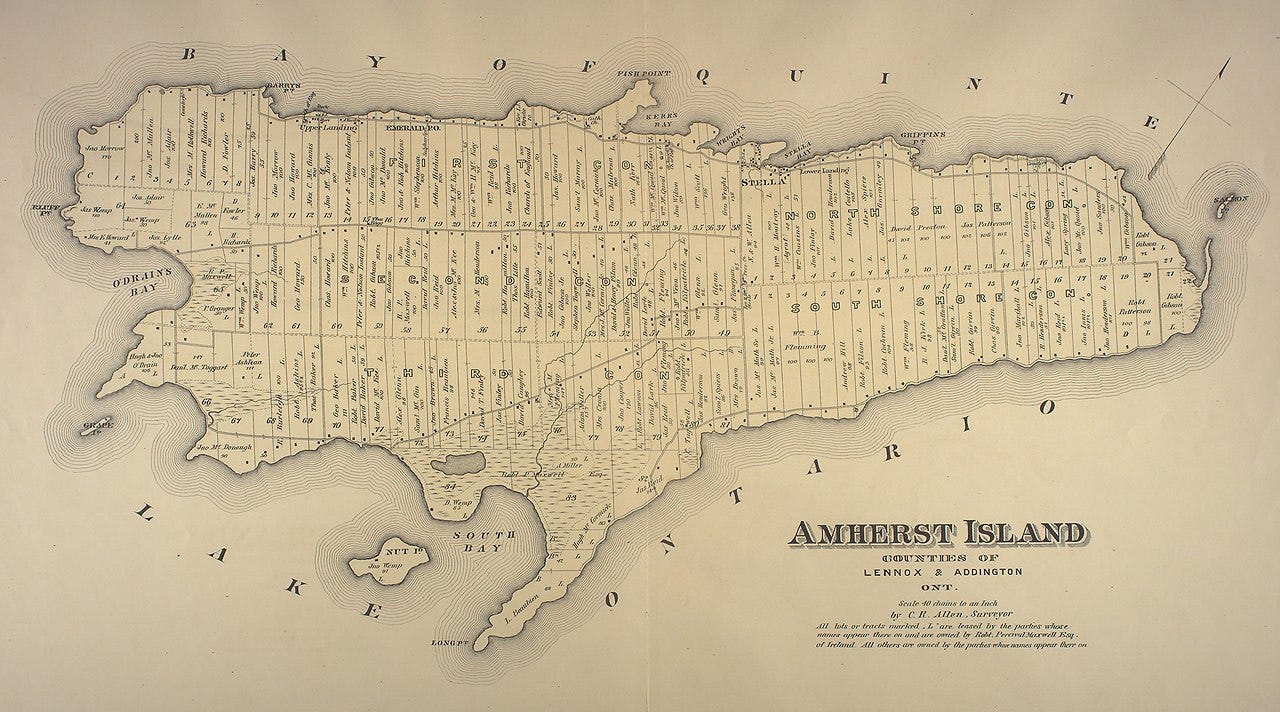

1878 map of Amherst Island, Ontario, Canada, from "Frontenac, Lennox and Addington Counties." Illustrated historical atlas of the counties of Frontenac, Lennox and Addington, Ontario. Toronto : J.H. Meacham & Co., 1878.

Moving away from the vile man whose name identifies this island without ever having lived there, to the figure who most personifies the natural beauty of the island, I introduce you to Daniel Fowler.

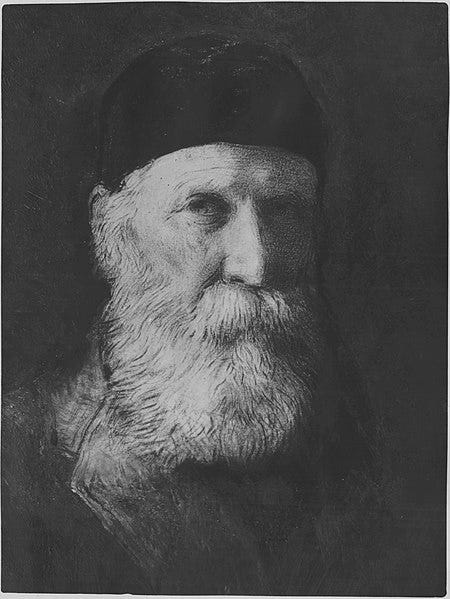

Daniel Fowler (1810-1894); photo (of portrait) courtesy Wikipedia Commons

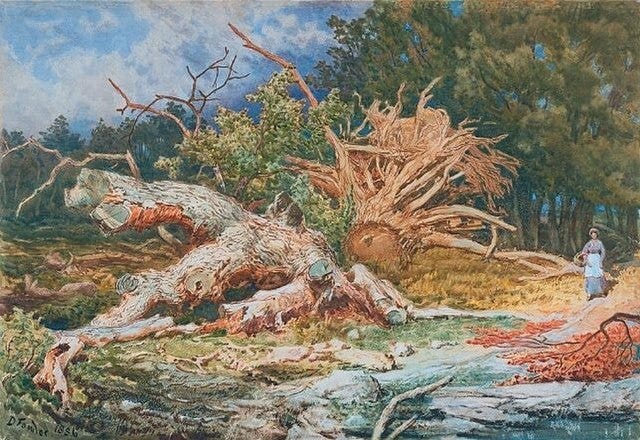

Fowler is now known as one of Canada’s most accomplished watercolourists, whose renderings of Amherst Island sit amongst other masterpieces in the National Gallery of Canada and other museums.

Fallen Birch (1886), artwork by Canadian artist Daniel Fowler. Watercolour on wove paper. 49.7 x 70.3 cm. In the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada.

He came to Upper Canada in 1843 from London, England, at the age of 33 with his wife, three children, a nurse and one of his brothers, following in the footsteps of his brother in law. He wasn’t sure that Amherst Island was the place they should settle, so they continued traveling west as far as London, but it soon became clear that the island had more charm (read: was a bit less ‘wild’ and reminded him of home). He came to North America on his doctor’s recommendation for the ‘fresh air’ (his health was compromised as the result of having had chicken pox eight years earlier and a brush with tuberculosis before that) as London was not the best place to raise a family, nor did it have much breathable air. He became a homesteader and set up his own self-sufficient 150 acre farm called The Cedars on the north west coast of the island (you can see the name ‘Fowler’ in two plots on the map above). Whether he knew how much work it would be, no one can say, but he clearly put his nose to the grindstone, so to speak, and did what he needed to do to take care of his family.

Just four years after building his home, it succumbed to fire and over a period of two years Fowler single-handedly rebuilt it — the same farmhouse that still stands today.

For 14 years after arriving on Amherst Island Fowler put aside his paint brushes and sketch pads. He wrote articles on various topics and was published in several local papers. In this article, he talks about the communal requirement for road building in the Upper Canada of 1863 and about how odd he found it seeing men of some education and importance doing such physical and ‘common-looking’ work - and then checks himself. He also waxes poetic about the absence of the bucolic walking paths that he enjoyed back in Britain …

Having mentioned a footpath, I must not leave unsaid that that charming feature of the English landscape, so characteristic of that country almost alone amongst all others,—that inestimable boon to the pedestrian and the lover of nature, winding through fields and woods, over stiles, and across streams, shortening and relieving the way, and unveiling scenes of the most exquisite beauty: dust and traffic left behind—does not exist throughout the length and breadth of Canada. The wayfarer must reach his point by a right angle, or a series of right angles; along straight roads, hideous with snake-fences and foul with frouzy weeds. Rather a harsh picture, perhaps.

Fowler didn’t simply build his own farmhouse, develop a working farm, paint and write. He also helped keep historical institutions alive, like the Pentland Cemetery, whose first grave was dug in 1831. He the first resident to donate money for the general upkeep of the cemetery (a massive $200 during his lifetime) and also planted a grove of cedar trees (a homage to his own farm, The Cedars) on the property, many of which can still be seen today. His grave is amongst those of neighbours and friends, whom he likely helped build roads alongside during those mucky summer days in the second half of the 19th century.

The grave of Daniel Fowler and his wife, Elizabeth (Gale)

(From Find A Grave web site, posted by Derrick B. #49691759)

I will surely visit this evocative and historical island again….