Do stories and films shape little girls' dreams?

How female protagonists and points of view are so formative to us as we grow...

I just finished watching a movie on Netflix called ‘This Changes Everything’. It is a documentary about the struggle women American film directors (and indeed, all women in the American film industry) have faced getting work in that business and thereby shaping what kinds of movies we all see. One of the executive producers is Geena Davis.

Geena Davis, as you’ll recall, starred in Thelma & Louise opposite Susan Sarandon in a 1991 movie that could only be described as a watershed in the way that it stayed true to its story arc - unrelenting to its very bold and inevitable conclusion.

But Geena Davis is much more than that. She is a member of Mensa (which means her IQ score is within the top 2%); shall we just say, she is WAY smarter than me. In 2004 she created The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, which works alongside the entertainment industry to increase the number of women who work within it. For this effort she was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2019 by the Academy Awards and the Governor’s Award by the Emmys in 2022. She tried out for the US Olympic archery team in 1999, but came in 24th out of 300 so didn’t get to compete - still, pretty good for someone who had picked up a bow and arrow only two years earlier and who had, by her own admission, very little athletic ability.

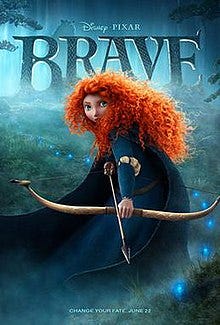

In the documentary, Davis says she wanted to see less Dicks and more Janes, hence the name of the website for her institute www.seejane.org. As an example of how media shapes the hearts and minds and bodies of young people, Davis’ institute measured young girls’ interest in taking up archery after 2012, the year in which both The Hunger Games and Brave were released - both with strong female leads.

Davis said:

“Our study is the first to examine whether archers in popular film and television programs inspire people to take up the sport,” said Geena Davis. “Both The Hunger Games and Brave were released in 2012; participation in archery rose 86% from 2013 to 2014, with women’s participation increasing 105% during that period of time! It’s not surprising to me that Hollywood’s depiction of inspiring female archers has contributed to the sport’s phenomenal growth — it’s another demonstration of the powerful impact fictional characters can have on girls’ aspirations. As I always say, if she can see it, she can be it.”

Now that’s downright shocking. In a good way.

When I was a girl, I don’t recall ever seeing a female protagonist in movies, let alone anyone to whom I could relate, even if their role was peripheral. I watched classic cowboy and Indian movies where, probably like many girls and young women, I saw myself inhabiting the “Indian” culture where a certain amount of animal and environmental sensitivity seemed to exist (with a feminine energy, I always felt), rather than the raw masculinity of the cowboy’s world, with violence and misogyny underpinning much of it.

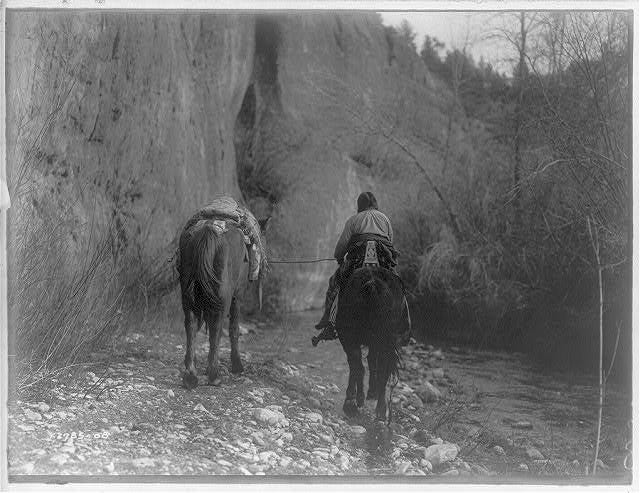

My vision was not characterized by Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s sidekick, but rather the lone brave who was often seen in silhouette against the western sky, resplendent with feathers, loose skins barely covering his body, a quiver on his back full of arrows, and a beautiful, sinuous horse - his companion - on whom he sat without the confines of a saddle. Ok, yeah, yeah, I know I’m romanticizing it but hear me out. This was exactly the image that was coming through in movies, paintings and staged photographs in the early 20th century and before.

Indeed, when I was young, as part of the neighbourhood gang we sometimes played “cowboys and indians”: the boys called the shots, no pun intended, and ran around shooting pretend guns, and the girls, representing the “Indians”, would be tied up loosely and left to fend for themselves in a garage. Of course I recognize now how perverse this was, but in those days it was just playing. Not even sure how this affected my psyche, except…

I would imagine myself, sitting bareback on my own perfect horse, without the need for a saddle, stirrups or reigns, just the two of us surveying the land and living naturally off of it. It didn’t matter to me that the images I had seen of “Indians” doing just that were all men. They seemed much more approachable to me than the cowboy.

The photograph above is considerably less heroic and more prosaic than that showing the warrior on horseback, and although it documents what might have been a routine occurrence, if I had seen it in my early years, I’m sure that I would have found it inspirational.

Could it be that I was attracted to characters who were self-actualized and living their lives independently, without the imposition of Western propriety and restrictive cultural mores? Um, yes.

Let’s look at some of the children’s entertainments I watched during my formative years in the 1960s.

I could grow up to be like Mary Poppins, a sugary sweet and magical nanny who wore lots of clothes and was surely a hoarder for all the stuff she carried around in her huge carpet bag; or I could grow up to be the nanny in The Sound of Music (again Julie Andrews, who my Dad adored, btw), who finally won her man after being saint-like with his children, unlike the condescending and superficial woman who was his wife. Or I could be Cruella de Ville, who schemed to kidnap an entire family of Dalmations so that she could slice them up and fashion a spectacular custom coat. Or, even worse, I could be insufferably optimistic like Hayley Mills in Pollyanna and end up tragically with both legs paralyzed, before having surgery that would hopefully correct them - a tear jerker if ever there was one!

But wait. There was also Pippy Longstocking, whose red braided hair and freckled head suggested trouble, and indeed she was, but in her own uniquely kind, free-spirited and generous way.

“In the orchard was a cottage, and in this cottage lived Pippi Longstocking. She was nine years old, and she lived all alone. She had neither mother nor father, which was really rather nice, for in this way there was no one to tell her to go to bed just when she was having the most fun, and no one to make her take cod-liver-oil when she felt like eating peppermints.”

Astrid Lingren (1907-2002) was Pippy’s literary creator; she grew up in a farm family in Smaland, Sweden, with affectionate parents who encouraged their children to do daily chores alongside playing and growing their hearts and minds. Lingren was quoted as saying:

"The countryside occupied every single one of my days from morning till night, and filled them so intensively... Our games and our dreams were inspired and nourished by rocks and trees."

A feminist, lover of nature and animals, first a single mother, then author and finally happily married with children and a successful career, she spent much of her adult life in the city of Stockholm. On the occasion of Lingren’s centenary, the Independent’s book reviewer Paul Binding mused on his 1994 visit with her and then characterized Pippi’s appeal thusly:

“Pippi's many acts of defiance constitute a good-natured protest against the tyrannies of convention, of being continually required to deny one's instinctive preferences. Pippi has something of the indomitable individualism of Huckleberry Finn, a character Lindgren loved, but she is not simply a girl boldly doing boys' things. In her panache and inventiveness she appeals to the longings, the secret psychic demands of girls and boys, and indeed has happily united them in readership all over the world (Lindgren has been translated into 91 languages).”

Indeed. Pippy was every girl’s, and boy’s, best friend and inspiration. Leave it to the Swedes.

On the other hand, there are these classic male dominated films: Swiss Family Robinson (with the only female characters the essentially invisible Mother, and then poor Roberta, who is the object of just about every male’s desire), The Hobbit, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Charlie Brown, The Jungle Book, the Sword in the Stone, Doctor Doolittle, Peter Pan, Gulliver’s Travels, Robin Hood — all with either no girls at all or with girls playing a secondary role.

But perhaps the single most spell-binding female character in my growing up years was Lucy, who was the youngest and most contemplative child in C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. She represented the power of adventure, trust and love and her compassion toward all the creatures of Narnia, including Aslan, was intoxicating to me. Her isolation from her siblings, her unwavering belief in that magical world, her special relationship with Aslan and finally, her crowning as Queen Lucy the Valiant — all ensure that she is indeed the heroine of this story, perhaps reflecting that we can be the heroines of our own stories.

“Lucy buried her head in his mane to hide from his face. But there must have been magic in his mane. She could feel lion-strength going into her. Quite suddenly she sat up.

"I'm sorry, Aslan," she said. "I'm ready now."

"Now you are a lioness," said Aslan. "And now all Narnia will be renewed. But come. We have no time to lose.” ― C. S. Lewis

What female characters in film or written word have had an impact on your life?

Always loved Pippi! Thanks for reminding me of her. Believe it or not, I used to run home from school when I was 9 and 10 years old to watch Adrienne Clarkson on Take 30. I know, very nerdy! She was certainly a woman in media that made an indelible mark on my perception of women. And then, I

really appreciated Bugs Bunny when he did drag. Can't say why, but there it is.