Knossos - Minoan history or mythic theatre?

Part I: Was today's Knossos fashioned from flights of fancy or rigorous archaeology?

Afterthoughts:

Usually afterthoughts come afterwards, but in this case I’m putting them at the beginning. Many months ago I promised a more comprehensive post on my visit to Knossos in Crete; I had suggested that my experience that day was just too momentous to allow for one right away. And yet, months later, I’ve recognized that understanding Knossos and my reaction to it is probably going to take years. I have already ordered four books on this ancient site and am completely and utterly hooked. This post is Part I of a series that I will publish as I learn and understand more…

Upon entering the cordoned grounds of the palace of Knossos, with my head in the proverbial clouds on Kephala hill, my lofty thoughts were brought right back down to earth when my friend said, “You know this is all fake, right?” Lo, behold; the Disney World that is Knossos.

Ever since high school when my art teacher introduced the empty vessels who were her students to the crown jewels of the ancient western world - namely, the buildings on the Acropolis in Athens and the brightly coloured columns and frescoes at Knossos in Crete - I was hooked. I don’t ever recall discussions of authenticity at the time; but I do remember quite clearly the decorative quality of the architecture and my teenage mind was puzzled how, amid these bleached ruins, the columns and frescoes were seemingly untouched by the vagaries of time. And for decades, I didn’t give it a second thought - until, at last, there I stood.

The truth is that the reconstructions of architectural elements and decorative frescoes that were done under the direction of the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in the years after 1900 have become nothing short of iconic. Not only had everyone, Cretans included, fallen under the spell of his vision but when he pronounced that the “myth” of King Minos and the labyrinth dwelling Minotaur were indeed true and that those storied events actually did take place at Knossos millenia ago, well, it became historical fact. Today, the “Palace” of Knossos is the second most visited archaeological site in the whole of Greece, just behind the Parthenon and its sister buildings on the Acropolis. One could say it is a cash cow for Greek tourism.

As we were led around the site on that perfect sunny day in May, one hundred and twenty-two years after Evans first began excavating on site, I struggled to understand what it must have looked like when he first arrived there - what was real and what was someone’s fabrication - and how Evans was so sure that his reconstructions were historically accurate - or did it matter? How much of what we see today is an elaborate fairy tale?

Today Sir Arthur Evans is considered the father of Knossos; erected in 1935, six years before his death, his heroic bronze bust stands at the entrance to Knossos where it towers above the visitor, his face showing the hint of a smile.

Let’s consider Knossos when Evans found it, at the turn of the 20th century.

The black and white photo below was taken in 1911 and shows Knossos a decade after Evans had already started work; even from this distance, it shows that the footprint of the complex resembled rubble, with fragments of columns, pathways, stairs, platforms, walls, cavities and underground passageways crumbled into the hillside.

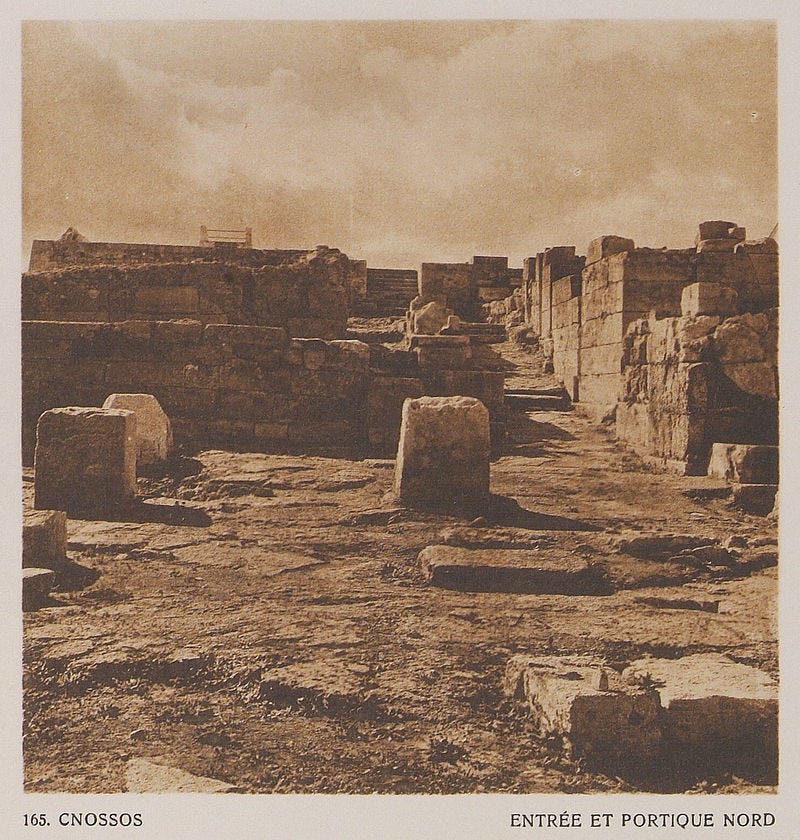

This next photo shows a view taken by German tourists visiting the site in 1919, showing the path alongside the North Portico that had yet to be fabricated, painted and erected by Evans’ team.

And this photo was one I took, showing the same vantage point but with the wall of the north portico completed, topped by the characteristic upside-down and brightly coloured Minoan columns.

As I begin to reconstruct my own feelings about the place, I am brought back to my first impression of the site as I stepped inside the entrance gates.

It was the haunted spirit of the ruin that immediately struck me, but not with the same purity and stillness that I felt at Delos. Still, even on this carefully choreographed tour, strung alongside other tourists within rope cordoned barriers, it was in the open air spaces, with the dancing pines and where the stones on the ground bore witness to the centuries of footsteps, that I felt the soul of ancient Crete.

But wait. Like so many stories that find their way into history, there is another one that has fallen into the shadows…until recently. Although it is through Evans’ vision and the hands of those archaeologists and labourers that he hired that allows us to see the colourful Knossos, another man preceded him both in vision and in digging.

Minos Kalokairino (1843-1907), born on the island of Kythera (off the southern tip of Greece) but making his home in Heraklion (5.5 kilometers from Knossos), was actually the first to perform excavations at Knossos. Kalokairino had pursued an education in law, but despite numerous attempts, successive family emergencies aborted his studies; he finally succeeded in 1901 at the advanced age of 58, a last ditch effort made even more essential because of his business failings and subsequent bankruptcy. His true love, however, was education; he saw himself as a man of letters, pursuing an interest in archaeology and ancient Cretan history. During the second half of the 19th century, Europe’s fascination with Hellenic archaeology precluded an interest in pre-historic Crete, so Kalokairino’s passion for ancient Greek mythology, especially the writings of Homer where mention is first made of King Minos and Knossos by Odysseus (see here) made his own mission more fervent.

Kalokairino’s excavation at Knossos was carried out in fits and starts through 1878 and early 1879, but the longest period of work lasted only three weeks during which a total of twenty labourers carefully removed about 500 antiquities, mostly of clay but also of stone and metal. A few of these were giant pithoi (clay urns) that made their way by agreement (not stealth) to museums in London, Paris and Athens; one that is said to be from Kalokairino’s excavation is in the present-day Heraklion Museum. Sadly, most of his excavated collection, as well as their official register, were destroyed when Kalokairino’s home was burnt during the violent uprising of the Cretans against the ruling Ottomans in 1898.

Despite Kalokairino’s archaeological success, indeed, probably because of it, the excavation was halted by the first Cretan Governor General who feared that the Ottoman authorities would abscond with the treasures, to feather the nest of the re-energized Imperial Museum in Constantinople.

After Kalokairino’s work stopped, he continued to herald the site’s importance to anyone who would listen:

Convinced too that his discoveries placed Knossos—and Crete—among the cradles of civilisation, he moreover did his utmost to make them known internationally. With pride, he escorted VIPs and scholars (whether archaeologists, antiquarians,

diplomats and other foreign delegates, newspaper correspondents, bankers and other wealthy individuals) round Knossos, and then showed them his private collection in the family mansion in Irakleio—now the Historical Museum. Among the visitors were T.B. Sandwith, J. Stillman, F. Halbherr, B. Haussoulier, E. Fabricius, C. Clermont-Ganneau, L.

Mariani, P. Demargne; and the great Schliemann, and Evans himself. Some of these visitors published brief observations, made drawings (e.g. Kopaka 1993) and photographs, and corresponded about the excavation and finds. Thus prehistoric Kephala at Knossos

entered the world’s literature as early as the 1880s (link).

Before Sir Arthur Evans ever directed a shovel be placed in the ground at Knossos and after Kalokairino’s efforts, archaeologists and antiquity scholars from around Europe (Britain (Sandwith), Italy (Halbherr), France (Hausoullier and Joubin), Germany (Schliemann)) and America (Stillman) had all jockeyed to be granted permission to excavate the complex - and Evans knew them all, after all, classical archaeology was a small world. It wasn’t just Evans who seemed to believe that this spot was the location of King Minos’ palace and underground labyrinth - they all did - and at this point, making history uncovering the earliest ‘Greek’ civilization outside of Mycenae on the Greek mainland seemed to be anyone’s for the taking. But there was still a lot of finagling that needed to be done; politics to be played, hands to be greased, lands to be purchased, deals to be made. Although over the years the Cretans had negotiated a system of local government that was nevertheless ultimately controlled by the Ottomans, any artifacts that might be seen as valuable would likely be claimed by the Turks and taken to the museum in Constantinople. It wouldn’t be until the Cretan Revolt from 1896 to 1898 (facilitated by the European powers of Great Britain, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia) and the resulting expulsion of the Turks, that work at Knossos could really take place.

Arthur Evans (1851-1941) had come to archaeology circuitously through his father, John Evans, who had at 17 started work at his uncle’s paper mill in Herefordshire, and very soon afterwards married his first cousin, his boss’s daughter, Harriet Dickinson. They had five children, of which Arthur was the eldest but was described by his own grandmother as “a bit of a dunce” (MacGillivray, J.A.; Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the archaeology of the Minoan myth; page 22). Arthur’s father took on partnership in the family business (later to be known as John Dickinson Stationary, a posh purveyor of writing paraphernalia) and his wealth and reputation grew. He, in turn, followed in his own father’s and grandfather’s footsteps by taking an interest in collecting artifacts, whether they be coins, shards of pottery or other buried curiosities. Arthur’s mother died when he was just seven years old and although he got along well with his two successive step mothers, he and his father spent much time together in hobby archaeological pursuits.

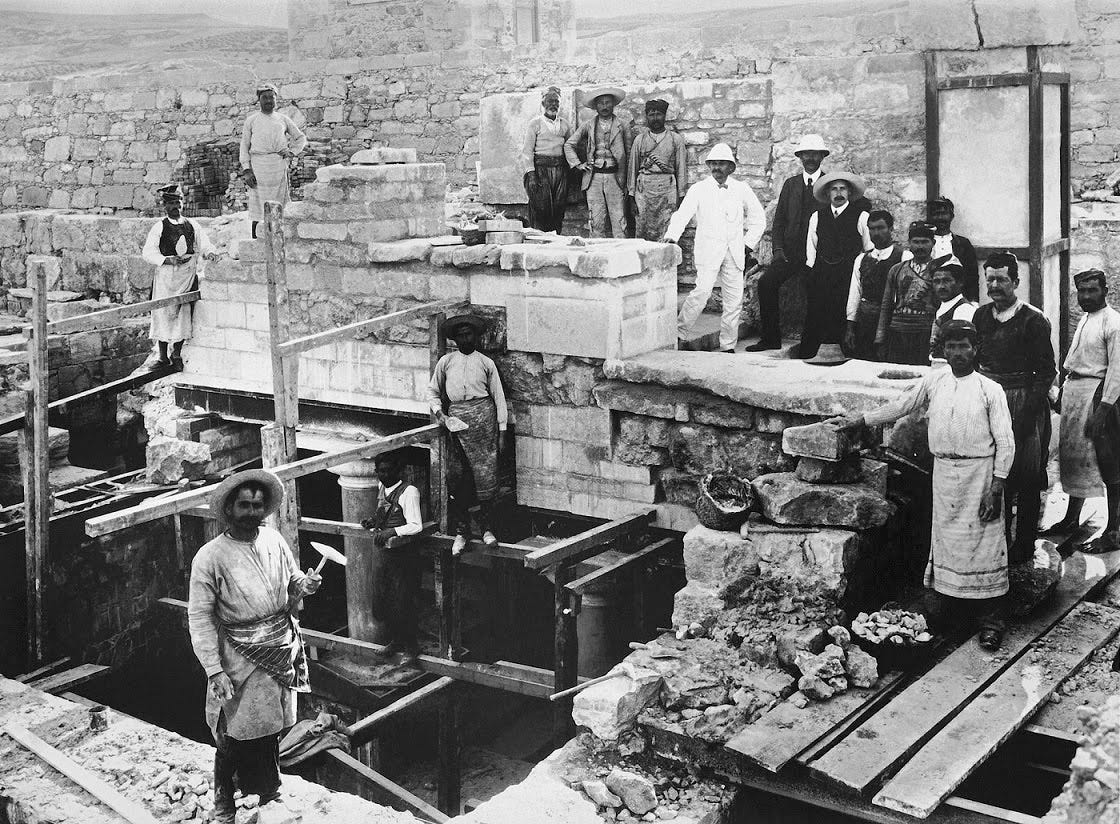

Despite having attended a distinguished prep school and then on to Oxford, Evans was allergic to the stress of examinations and did not do well academically. Add to this his cocky, somewhat charismatic and devil-may-care personality, which contrasted with his diminutive stature (he was not much more than 4’ tall), his compromised eyesight (short-sightedness and night blindness) and his affectations (he carried a trademark cane which he had named ‘Prodger’), Evans garnered a name for himself in erudite circles. He is pictured below with the Knossos work crew, in a pristine white suit with matching pith helmet and standing, hand on hip, strategically above the rest.

But what compelled Evans to come and pursue the secrets that Knossos offered? Come back for Part II for more on the mysteries of Greek myth and the Bronze Age Cretan ruins that slowly divulge those secrets even today.