The Jewel in NYC's Central Park

Within the Conservatory Garden, you'll find a colourful and restful paradise

New York City has its share of botanical and natural wonders: both the New York and Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, Central Park, Fort Tryon Park, Wave Hill, Battery Park, Bryant Park, Washington Square Park, the High Line, Hudson River Park….there are many green spaces to enjoy. But it wasn’t always this way.

City parks almost everywhere have repeatedly suffered from lack of government funds and lack of vision but then many of them have also risen from these setbacks with tremendous success. This is the story of one of these gardens — the Conservatory Garden, which is perhaps my favourite New York City garden of them all.

If you walk north along Fifth Avenue skirting Central Park on your left, you will see an ornate wrought iron gate just before 105th Street which was donated by the Vanderbilt family but now marks the entrance to the Conservatory Garden. You are now where North Manhattan meets South Harlem, but if you enter through this gate, you have found what feels like paradise.

The Conservatory Garden comprises six acres in Central Park and is divided into three sections: the central section is Italianate in design, green and formal, with a jet fountain and curved wisteria covered pergola as its focal point in the ascending distance; to the right is a French style garden, with tightly planted parterres encircling a playful fountain — this garden has two display seasons, one showing off spring bulbs, the other with fall blooming chrysanthemums; the third garden is on the left, and is the most colourful and interactive, with wide walking paths surrounding a hidden and partly shaded waterlily pond. This is the one I’m going to be featuring.

But first, some history.

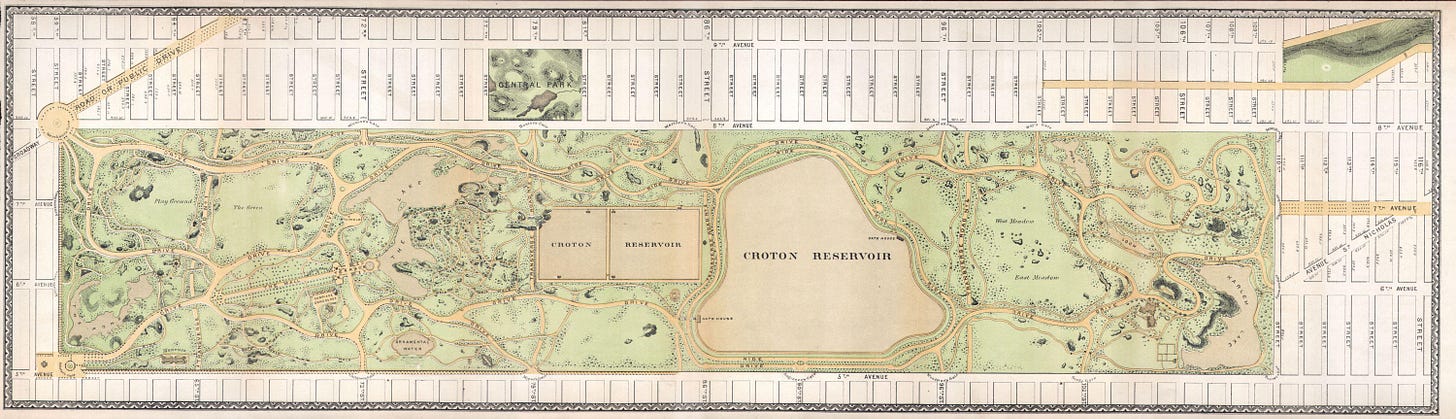

The landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead and architect/landscape designer Calvert Vaux won the design competition in 1857 to create the public green space that is Central Park, and almost twenty years after work began, the 778 acres of city oasis opened to all. Sadly, a settlement of over 250 African Americans was unceremoniously dislodged and forced to relocate in preparation for the park’s construction - but that’s another worthy story for another time.

Originally the site of the Conservatory Garden was meant to be an arboretum, but the funds were not there to see this through; indeed, a greenhouse (or conservatory) stood in the area from 1898 onwards, hence its name, which showcased a dizzying display of plants and flowers. Other glasshouses were in the vicinity as well, which provided workspace to propagate the trees and shrubs, and the environment to grow them on, that would be planted in the park.

In the early 20th century, about thirty years after it was created, the park entered a slow decline — first the years leading up to and including WWI and then the excesses of the Roaring 20s. The park had become a playground for the wealthy, and politics had prevented it from becoming a park for working class people, those who most needed its respite — signs asked people to stay off the grass, with only about 9% of the park designated for ball sports in 1926. Interestingly enough, the well-heeled League of Women and Federation of Women’s Clubs were among those opposed to having playgrounds in the park, rather wanting it to be a quiet and peaceful place of rest rather than full of shouting children — likely a haven for those very mothers who could get away from their own noisy offspring! And in the middle of it all, the Central Park Casino became one of New York city’s most expensive nightclubs, as well the Mayor’s adhoc office and a gathering place for his cronies.

Everything changed again when the new commissioner, Robert Moses, took the reins and finally started to transform and re-brand it through the 1930s — by the way, he made it a point to replace the casino with a playground. The design of the Conservatory Garden was put in the hands of Gilmore D. Clarke, a landscape architect who worked with Moses on a tremendous number of area park projects (he is the one to thank for the beautiful stone bridges that you can still see throughout the state and Westchester County), and the planting plan was developed by M. Betty Sprout, who had received a B.A. in landscape architecture in 1928. The designs were put in the ground in 1937 by workers hired as a part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal initiative to counteract the devastating economic impact of the Great Depression. It was open to the public that same year, but without the namesake conservatory, as it had fallen into disrepair and demolished. Sprout and Clarke must have found kinship in this project and married soon afterwards in 1941, and she continued to work on public planting designs, often alongside her husband, until her early death in 1962 at 55 years of age.

Then came the Second World War and afterwards, the city’s fiscal crisis, until the condition of Central Park hit rock bottom in the 1970s as it became known as one of the darkest, garbage filled, overgrown, crime-ridden and dangerous places in New York City. Enter another period of rejuvenation spear-headed by the Central Park Conservancy, which was born in 1980, propelled into existence by the well-heeled community in Manhattan who wanted to see their beloved green space saved. On board were such names as Ed Koch (then Mayor of NYC), Edward Soros (who helped finance the multi-million dollar Central Park Community Fund), Gordon Davis (Parks Commissioner, lawyer and civic leader) and Elizabeth Barlow Rogers (she was a landscape designer, preservationist and writer — and also the park’s first Administrator and then, first president). William Sperry Beinecke (the corporate businessman and lawyer — his family owned the Sperry & Hutchinson Company — and philantrophist) was appointed by Mayor Koch as the inaugural chair of of the board of the Central Park Conservancy and selected its members, as well as creating a ‘Founder’s Committee’, packed with the rich and famous, movers and shakers, all willing to put their faces and money behind this effort — they included Brooke Astor, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Paul Newman, to name but a few. Beinecke later recalled that one day he walked into the city’s Parks Department to ask how he could help rejuvenate Central Park, after looking out onto it from his Upper East Side home, and seeing what a dump it had become.

I am reminded that one Saturday in the summer of 1986 when my husband, at the time, and I had driven into Manhattan from Long Island where we lived (we were poor graduate students) to visit a museum. When we emerged at closing, we discovered that the hood of our old Dodge Duster had been popped and our battery had been stolen. We ran around like chickens with our heads cut off, taking a shortcut through Central Park to find a garage that would sell us a used battery. We finally did so, but I remember the sheer terror I felt even then upon entering the park at dusk, thinking that we’d be murdered on the spot. We joked afterwards that the folks at the garage had probably stolen our battery and sold it back to us. That purchase depleted our already meagre bank account!

The designer responsible for the way the Conservatory Garden looks today, Lynden B. Miller, trained as an artist and painter early in life, but the lessons she learned at the private girl’s school she attended in Manhattan likely helped drive her into a life where she worked toward the public good through gardens. She is quoted here in the Chapin School newsletter from 2016 below:

"I was telling my own granddaughters the other day, that at Chapin, through Miss Stringfellow in particular, you were taught that women could make a difference, that it was important to be a woman. Essentially," she stated. "At Chapin, I was taught that it was important to do the right thing to make life better for others."

When she was called upon to help restore the Conservancy Garden, as she had also trained as a horticulturist at the New York Botanical Garden, she truly found her lifelong calling and put down her paintbrushes. In 2010, she published her first and only book entitled, Parks, Plants and People: Beautifying the Urban Landscape, where she makes her case for enhancing our quality of life through beautiful city spaces.

It takes millions of dollars, most of it raised through corporate and private donations as well as endowment monies, to not only keep this garden going but to furnish funds to renovate and upgrade it. As we speak, a new restoration initiative is taking place, with the areas of concern being the bluestone paving (that you can see here in the walkways of the Secret Garden), upgrading the infrastructure including the fountains and water features, creating ramps for accessibility, renovating the architectural and structural features of the garden (including the wisteria pergola in the centre garden) as well as all the benches, railings, retaining walls and stairs, and improving the drainage.

The beauty of this garden is not only in its colour, but in its scale. This planting incredibly incorporates almost only annuals but it has the presence of a shrub border. Sunflowers, red fountain grass, Japanese maple treated as a red-flowered annual, coleus, canna and many other plants are used not only for their flowers but for their foliage colours and shapes.

The garden uses boxwood hedges that are clipped tightly to remain about two feet tall, with a dark green face and flat topped profile — they provide a sinuous spine that ground the riot of colour and texture that hugs it, front and back. The combination of the two gives great dimension to the garden. Here we see perennials, evergreens, shrubs and tall grasses used as a backdrop, while shorter annuals and tender perennials parade in front of the boxwood, mirroring and complementing the colours behind.

The leaves of canna, golden sweet potato vine and artemisia are effective here in the sun, with flowering plants in hot reds, oranges, coppers and bronze.

This view shows pastels in soft, billowy inflorescences, contributing to the romantic feel of this garden. In the right foreground are one of Miller’s signature plants, the lime green and demure Nicotiana langsdorfii. You can see in this picture how the pavers are already beginning to crack and lift — and this was over 10 years ago.

The central piece de resistance in the Secret Garden is this pond, filled with waterlilies and goldfish, surrounded by curved viewing benches, graceful grasses and roses. At one end is a bronze statue and fountain by Bessie Potter Vonnoh, depicting the two main characters in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s romantic story describing the transformative power of gardens, The Secret Garden.

There was not a moment that went by when I visited that there was not a procession of birds enjoying the bowl full of water which Mary holds aloft, constantly refreshed for their pleasure.

The garden here provides many lessons, not least of which in plant combinations (shouldn’t that heuchera want more shade? who would have thought to poke some dill in there?) as well as being adventurous with your choices.

I heartily recommend a visit when you’re next in New York. In the meantime, you can take a look at Miller’s list of plants here and plan for your own colourful extravaganza!